In one of his early responses to the derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg referenced the apparent common phenomenon of derailments in the United States. Whether to downplay or simply place it in context, Buttigieg stated that around 1,000 trains derail every year – around three each day on average. Is this a railroad crisis? Why does this happen so frequently in a developed country?

Buttigieg is correct that the U.S. experiences around 1,000 derailments each year on average – although this is of no comfort to those impacted by severe ones. The type that occurred in East Palestine are vanishingly rare as a statistical matter – in no small part because the intentional release and burning of hazardous materials is almost unheard of in this type of situation. And that is why observers would be wise to view the derailment in Ohio as a distinct issue from the plumes of smoke – the two are related, but not causally. In other words, the derailment created the conditions that led officials to burn the chemicals, but the derailment itself did not cause the black plumes of smoke, that was a secondary decision made days later.

In context, setting aside the practice of releasing hazmat and burning it, derailments like the one in East Palestine are also rare because over the last two decades, fewer than one percent of all train accidents involved the release of hazardous materials. This is attributed both to improvements in rail safety that have lowered the level and severity of collisions and derailments, but also to increasing standards for rail cars and tankers, which are designed to withstand impacts and punctures, and which feature pressure release valves for situations like this.

While that may help shed light on why hazmat disasters are less common, it does not yet explain derailments themselves. Why are there a thousand derailments and what does that mean in context?

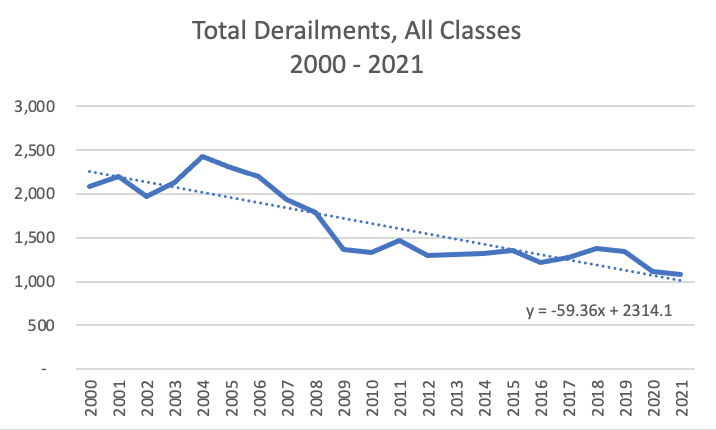

Since 2000, the rate of derailments in the U.S. has fallen by 37 percent, according to data from the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). Even since 2020, the rate has fallen by around six percent. Derailments have even fallen at a faster rate than general train accidents. For all train accidents per million train-miles – a figure that would include derailments – there has been a decline of 33 percent since 2000. That means both that rail is getting safer and that derailments are happening less frequently over time. Data for 2021 indicates that there are approximately 1.85 derailments per million train-miles. But because trains move nearly 600,000,000 miles every year, that means around 1,000 derailments still occur.

Focusing on the derailments is important, and we should strive for zero derailments. But it also misses the incredible amount of economic and social benefit that takes place and the millions of miles moved without any derailments.

The primary issues causing the thousand annual derailments include things like equipment failure, track deficiency, and human error. In proportion, these are 43 percent from track, 30 percent human error, 13 percent equipment, and the remaining from signals and miscellaneous causes.

The solutions to derailment must center around the actual causes. A rush of proposals came out in the wake of the East Palestine derailment and ensuing environmental crisis, yet many of these would not have made a difference. One example is train crew size, where the Biden administration is working on a proposed rule that would require every moving train have at least two qualified individuals in the locomotive. Not only is there insufficient data to justify this rule, but the train in question had three individuals, so even if the rule were finalized it would have had no impact.

At issue with the Norfolk Southern train that derailed in East Palestine was an overheated wheel bearing failure, according to the preliminary report from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). In context, wheel equipment-related train accident rates have declined by 43 percent since 2000, coming in at a rate of 0.056 accidents per million train-miles in 2021. Axle and bearings-related train accident rates have similarly declined by 49 percent since 2000 and are at 0.042 accidents per million train-miles for 2021. And while the ten-year trend for axle and bearing issues has plateaued, there is room for improvement, as the previous five years indicate a potential marginal rise in these accidents. Increased placement and sensitivity of sensors along the track may help address this.

Track issues lead to the most derailments, and while human error comes in second, track issues lead to nearly twice the cost of human error. Equipment failures result in nearly 20 percent of the costs of train accidents. Reforms and improvements should center around these in their proper proportion and based on data. Policy solutions and private investment should seek to protect worker and public life, the environment, and infrastructure – a balance that requires incorporating accident numbers and costs. By and large more and better technology is needed to address these issues.

So why are there 1,000 derailments in the U.S. every year? The answer is that this is primarily the natural consequence of our supply chain – when lots of trains are moving, there will be accidents. In proportion, it is a sliver of the total picture of rail and not representative of their overall safety, which move millions of train-miles every year without incident. Moreover, while it remains true that around a thousand derailments occur annually, even this number is uniquely low historically and is on a downward trend from the past two decades.

More and better technology is needed to keep improving safety, and incidents like East Palestine are critical to investigate and fully understand. But they should not be an opportunity to push policy proposals that are not relevant to the issue at hand, and the confluence of other factors like the burning of hazardous materials should not be directly linked to the derailment itself.

Written by Benjamin Dierker, Executive Director

The Alliance for Innovation and Infrastructure (Aii) is an independent, national research and educational organization. An innovative think tank, Aii explores the intersection of economics, law, and public policy in the areas of climate, damage prevention, energy, infrastructure, innovation, technology, and transportation.